It’s not even 11 p.m., and the house is already trashed. Empty beer cans line the window sills, people are ashing cigarettes into plastic cups and someone’s puking in the bathroom. The floor is sticky, and the iPod DJ is playing “Gasolina,” while the host is running around with a garbage bag, frantically trying to clean up the mess. It’s all pretty average by house party standards, but in 2025, everyone still wants to relive the nights they can’t remember.

House parties these days are rare. With rising rent prices and shrinking living spaces, most people can barely afford to throw one, let alone live somewhere big enough to host. Plus, young people are drinking and going out less, preferring more intimate hangouts over loud clubs or massive gatherings. But even with these shifts, house party nostalgia is alive and well — and it’s making a comeback with Gen Z.

Charli XCX strolls through a trashed house in “party 4 u,” while The All-American Rejects play pop-up shows in fans’ backyards. Viral TikTok clips of wild house parties fuel the trend, and Londoners are lining up to see House Party’s suburban home set-up. Meanwhile, Lab54 has been leading the charge, hosting dorm parties, kitchen raves and even an IKEA-sponsored “housewarming” event series. But what’s behind the actual boom?

At its core, it’s about nostalgia, a longing for what seems like a simpler time when house parties were about cheap beer, questionable music choices and a sense of spontaneous fun. For Gen Z, who grew up during the pandemic, the idea of a packed house party with a bunch of strangers feels like an exciting night out, especially as something they missed out on during their teens.

As Angie Meltsner, founder of cultural insights and trends research studio Tomato Baby, puts it, “People are craving the spontaneity and unpredictability of house parties. Those are the kind of moments you don’t get in the same way outside of a house party setting.”

She adds that a house party offers a more intimate vibe than a club, but still comes with the thrill of unpredictability. And as Retro Avocado’s Janine DeMichele-Baggett points out, there’s also “a little bit of danger,” whether it’s sneaking out past curfew or the cops showing up. It’s the kind of stuff you see in the movies, where the house party is seen as a place of havoc and lawlessness. And who wouldn’t want to experience that?

For DeMichele-Baggett, a content creator who specializes in ‘90s and ‘00s nostalgia, Gen Z is fascinated by what they’ve missed out on. They comment on her viral videos of college house parties, expressing jealousy over an era they couldn’t experience firsthand.

“People want to have that feeling of wild abandon, but now it feels like that’s not allowed,” she explains. “Think about the kids growing up in the pandemic wanting to party with 100 people in a house, but being told that’s the worst thing ever. And I think that’s probably a big part of the appeal, because that seems like such a taboo thing.”

For many of them, the house party represents a rite of passage they never had. As Meltsner puts it, Gen Z is getting the chance to live out the parties they missed in what’s a kind of delayed rite of passage. “So hopefully it’s a sign that the bubble of isolation is popping,” she adds.

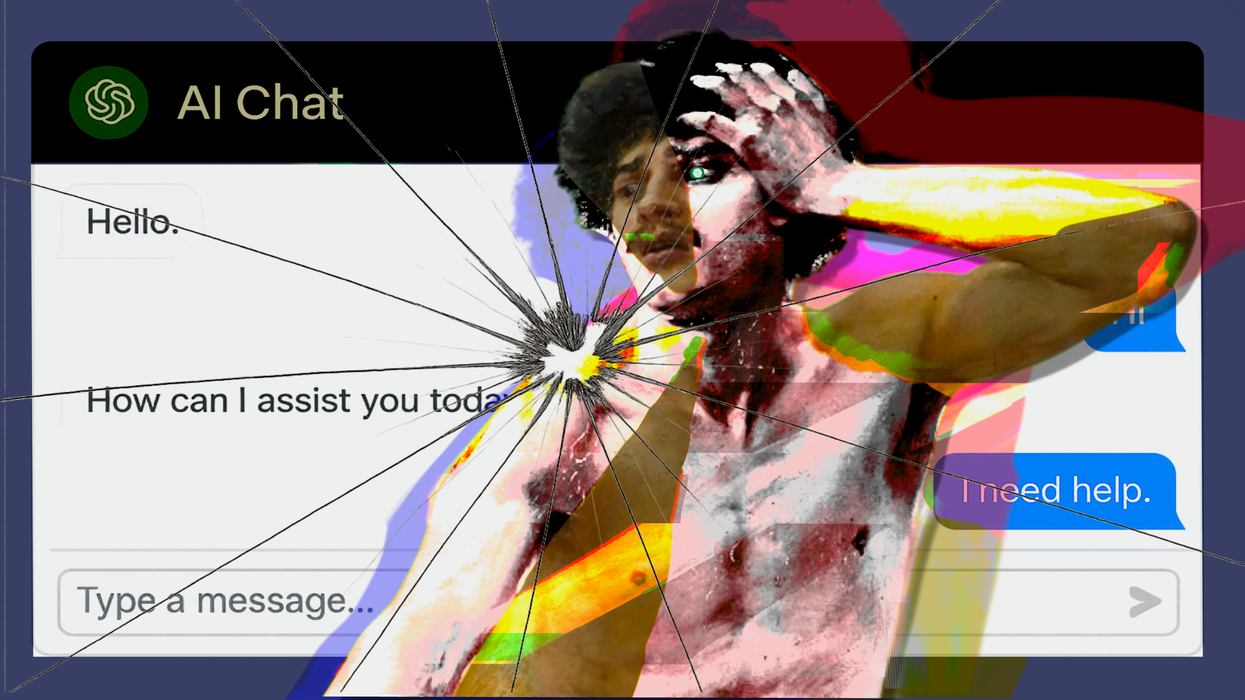

But maybe the biggest draw of house parties is the escape they offer from the curated perfection of social media. As DeMichele-Baggett says, people are tired of having to craft every moment and present the perfect image, while “millennials had the freedom to be ‘cringe’ and just be themselves.”

“Gen Z doesn't know what it's like to party like, without it being viewed as, ‘This could end up on the internet later,’” DeMichele-Baggett says. “People are so much more worried about what they look like and trying to get good pictures. But I have pictures from house parties, where I’m a hot mess.”

Perhaps this frustration with the pressure to perform and look perfect is leading more people to embrace the chaos of house parties, which Meltsner agrees with before noting a growing desire for “relatable flaws and messiness.” It’s a place to let your guard down, where the mess is part of the charm. So with this push against curated posturing, it makes sense that people would want to take part in the celebration, even if there are a few missteps.

But there’s something deeper happening here, too. The world feels uncertain right now, and sometimes, it’s easier to lean into the chaos than try to make sense of it all. After all, as Meltsner says, “embracing the chaos and indulging in a sense of hedonism is part of a reaction to a macro level of uncertainty.”

She adds, “And those are really strong descriptors of what a house party is all about.”