Prague, August 1968. Soviet tanks roll through the streets. In a cramped studio near the Vltava River, sculptor Karel Nepraš bends wire into skeletal frames, wraps them in fabric, and paints them an aggressive red. The result is Large Dialogue (1966): two figures locked in conversation, except they're skinless, monstrous, utterly wrong. Their cavities gape. Their proportions scream.

In criticizing the regime, artists risked disappearing, but by making something that felt wrong, that screamed through its distortion, artists could speak. By the mid-1960s, a loose movement Czech critics would later call "Czech Grotesque" had figured out that under censorship, distortion could say the things words could not. Artists like Nepraš, Jan Koblasa, Aleš Veselý, and filmmaker Jan Švankmajer built a visual language where distortion was the medium. When the state becomes monstrous, make monsters and let bodies do the talking.

This turn toward distortion had deep roots. Czech artists had been fracturing reality since before the war. Pre-WWI Czech Cubism applied geometric fragmentation not just to painting but to architecture and design, establishing a national habit of breaking down forms and making everyday objects strange. Then came the Prague Surrealist Group of the 1930s, one of the most vital outside Paris. Artists like Toyen and Jindřích Štyrský, alongside theorist Karel Teige, built a visual vocabulary of psychological unease and dark absurdity. Švankmajer would spend his career mastering that language.

The Nazi occupation from 1939 to 1945 banned the Surrealist Group and forced artists underground. After the war came a brief window of freedom, then the Communist coup in 1948. The new regime targeted Surrealists because Karel Teige had published a 1938 manifesto, Surrealism Against the Current, equating Stalinism with fascism. Surrealism was banned again. Artists who'd learned to encode their work under the Nazis adapted the same techniques for Communist censors.

The Grotesque inherited these tools and sharpened them for new pressures. The Prague Spring of 1968 brought a brief, intoxicating thaw. Under Alexander Dubček's "socialism with a human face" reforms, censorship loosened. Artists exhibited openly. For eight months, direct speech seemed possible again, but the Czech drift away from totalitarian control found elsewhere undermined the communist project. The Kremlin noticed, and the Soviet tanks rolled through Prague.

Many Czech artists abandoned literal approaches entirely. Švankmajer's 1968 film The Garden shows a man visiting his friend's suburban home, where every interaction becomes an absurd ritual. People transform into hedges. Conformity consumes identity. Nobody says "totalitarianism is dehumanizing," but you feel it in your gut watching a man become topiary.

Small galleries mounted exhibitions at dusk and dismantled them by morning. Švankmajer's puppet films screened once in basements before "committees" suggested revisions that would gut their bite. Artists moved between official work and covert projects, sharpening their edge in private. The distortion, the ugliness, the deliberately botched proportions became the semiotics of dissent.

Nepraš was part of the Křižovnická School, a group that met at Prague pubs and called themselves the "Crusaders' School of Pure Humor Without Jokes." Absurdist, self-aware, serious about not being serious. They understood that dark humor was plausible deniability.

Czech Grotesque artists made you physically uncomfortable on purpose. When you look at Nepraš's Moroa series (1965–67), the skinless homunculi Frankensteined from industrial materials, your body reacts before your brain catches up. The hands feel overworked. The mouths refuse the smile. The wires and hoses look like infrastructure turned inside out, exposing the plumbing of control.

Švankmajer took this further in The Flat (1968). A man enters an apartment that transforms into a hostile environment. Objects attack him. Space warps. Eventually, all that remains is his name, Josef, scratched on a wall. Kafka by way of stop-motion animation. You feel the paranoia of living under surveillance without a single shot of a secret police officer.

The system of oppression was fragile, and Czech artists refused to pretend society was anything more than a funhouse mirror. The language of the upsetting and bizarre acted as a finger pointing out the ubiquitous malignancy of control.

Where Švankmajer’s walls closed in, Nepraš’s bodies exploded outward. He painted his monsters bright red. The color of revolution co-opted by bureaucracy, turned into a mockery of itself. The communist authorities hated him for it. His 1960s work Family Ready to Depart was demolished on government orders. He was banned from exhibiting between 1974 and 1988, essentially erased during "normalization."

Not all embers of dissent were as readily snuffed. Community formed in galleries where people gathered to stare at work that was defiantly, beautifully wrong. The act of showing up was itself political. The people who made the effort to find a small gallery at dusk were already primed to look for deeper meaning. Simply being in the room together, breathing the same air while staring at something purposefully wrong, created the commons.

The 1987 exhibition of Czech Grotesque art made this unspoken conversation public. For nearly a decade, Nepraš and others had been invisible, their work confined to private studios and whispered recommendations. When the City Gallery finally mounted "Grotesqueness in Czech 20th Century Art," people came to see work they'd only heard about. They stood in front of Nepraš's red monsters and laughed. The laughter meant: I see what you did. I see what you're saying. Curator A. Pomajzlová framed it as "a horror of life and a way out of the bleakness of the time." The Berlin Wall was two years from collapse.

The Czech artists had clarity of target: the state, the censors, the tanks. Their monsters spoke to people who showed up to galleries at dusk, who chose to look. The method worked because power operated through banning and hiding. Make something that looks like nonsense, and it could slip past.

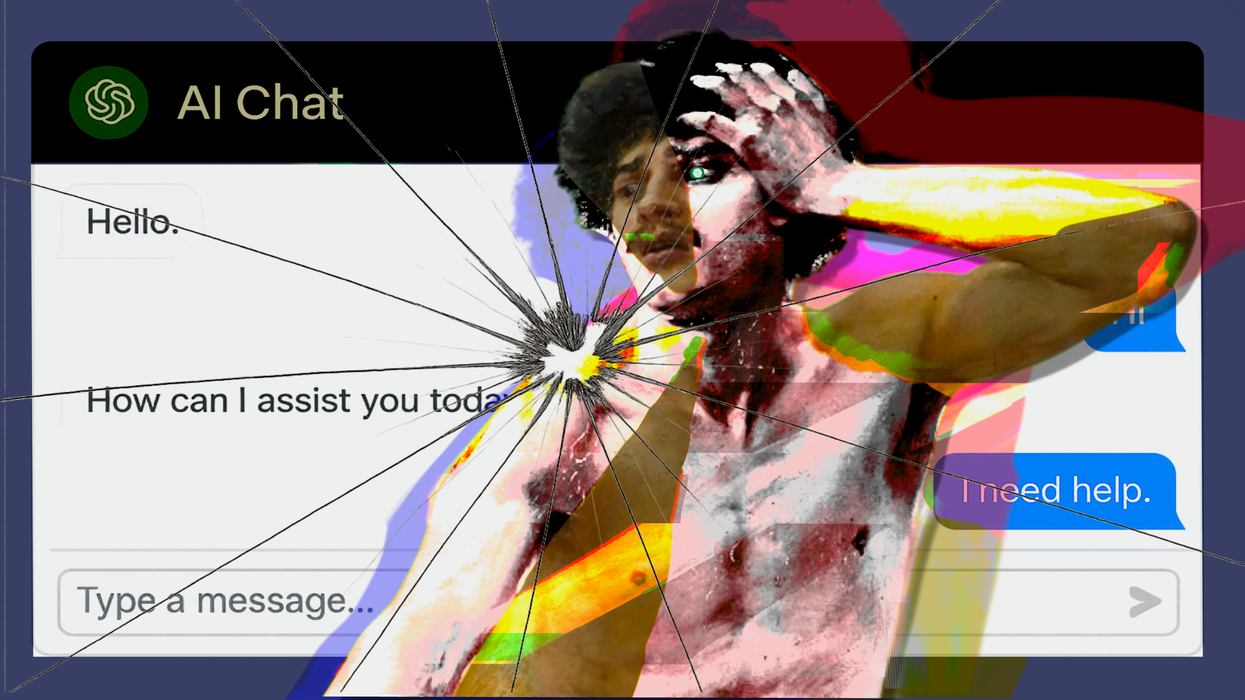

Today's systems don't work that way. Censorship has largely been replaced by optimization. Algorithmic feeds don't ban the uncomfortable. They measure it, monetize it, feed it back as content. The algorithm doesn't care if you're disrupting it. It cares if you're clicking. Distortion gets processed as engagement, packaged as an aesthetic for people who like feeling uncomfortable. The grotesque gets tagged, recommended, sold.

Which means the tactics that worked in Cold War Prague might not transfer. Or they transfer only as performance, as content about resistance rather than resistance itself. When control operates by making everything visible and consumable, what does wrongness even look like? What form could refusal take that the system wouldn't immediately recognize, capture, and optimize?

I don't know. And I suspect that's the point. Every system of control invents its own aesthetics, and every mode of refusal has to be illegible to the thing it's disrupting. The grotesque wasn't a style you could copy. It was a response to specific conditions: conditions where you knew exactly who was watching and what they couldn't allow.

Our conditions are different. We might not recognize what refusal looks like now because it hasn't been invented yet. Or because it's already here, operating in ways we can't see. If we look for the systemic dissent born of Prague, we won’t find it. If there are lessons to draw from the Czech Grotesque, it’s that every age must invent its own monsters.

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)