Scroll long enough in 2025, and you’ll eventually land in 2016. A year cast in Valencia-filtered nostalgia, it was the heyday of Vines, King Kylie and entire rooms belting “Black Beatles” like it was the national anthem. It was a time before the internet got meaner, before TikTok brainrot took over feeds and before influencers became lifestyle brands. And now, nearly a decade later, people are longing to return to that moment, when their biggest worry was squeezing in one more round of Overwatch before Mom called them downstairs for dinner.

On TikTok, there are over 300 million videos tagged #2016. In them, people revisit the Pokémon Go craze, pay homage to beauty guru–era makeup and share hazy edits of Unicorn Drinks and Coachella flower crowns. There are snippets of ragers soundtracked by Lil Uzi Vert, dancers dabbing and viral clips of people reminiscing about teenage nights spent driving around past curfew — music up, location off. In the comments, users share their own memories or express envy, all idealizing a time that felt spontaneous, carefree and real.

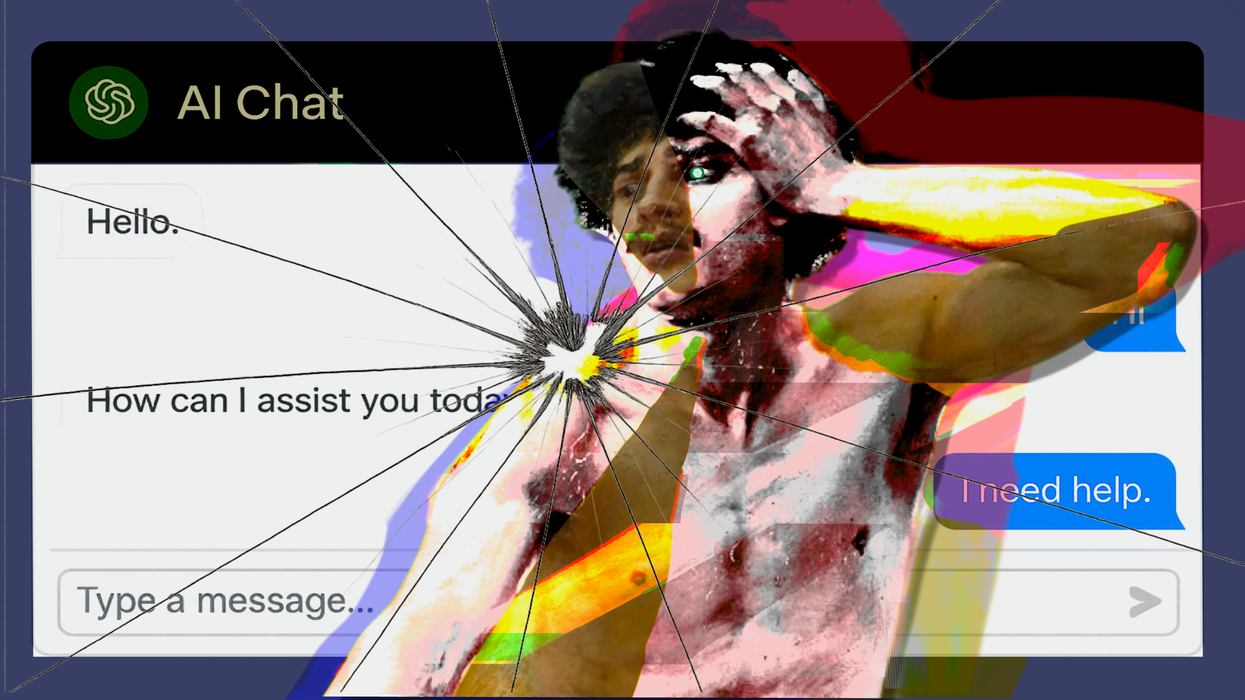

But beyond the prank videos and Snapchat dog filters lies a deeper craving. It’s not just a craving for a less curated life, but for one that felt unburdened. A time that younger people are now romanticizing not just as an aesthetic, but as a moment when the future still felt bright.

“American Gen Zers face an uncertain future, an abysmal job market, astronomical costs of living and dehumanizing legislation,” says Heather Hayes, clinical assistant professor of media and communications at Pace University's Dyson College of Arts and Sciences. “Their yearning for the inimitable perfection of 2016 is not too surprising.”

Hayes recalls the year firsthand, describing it as a time when “the thought of getting older and growing up was still exciting.” But that sense of optimism, she adds, has since faded, as Gen Zers “no longer feel that way about their futures.” Instead, they look towards an era that feels comfortingly familiar, even if they were slightly too young to fully experience it.

While “every generation has that idyllic time in the past they yearn for,” Hayes points out that Gen Zers — now 13 to 28 — have endured two major collective traumas since then: the Trump administration and the pandemic. Together, they fractured Gen Z’s formative years, turning the future from a promise into a question mark.

“And with the economy and all the fucked up shit happening in the world, we’re just wanting to return to something simple and familiar,” says Misha Gawfic, 27. “Nostalgia is the most accessible thing right now.”

Gawfic was in high school in 2016 and remembers it as “a really colorful year,” full of fun music, silly filters and house parties straight out of a teen movie. “It was a really easy time,” she says, noting that younger Gen Zers may long for a version of 2016 they never fully lived, but wish they had.

@nostalgia.moments.0 2016 was the best year ever❤️👇 - #2016 #nostalgia #fy ♬ Originalton - NostalgieThrowback🚀

Others like Dylan Greathouse, 19, say the pull is more personal than cultural. As someone who was in elementary school, he remembers the year as “when we were kids.”

“It’s kind of a golden time in your life,” he says. “You’re not too worried about school. You’re just out having fun all the time.”

He points toward the rise of YouTubers, the release of landmark video games and an explosion of music and memes that made everything feel vibrant. And that cultural wave happened to align with a moment of pure childhood joy.

“I just remember being carefree and loving all these things,” he adds. “There were a lot of good things happening on the internet. I don’t remember the bad stuff.”

That carefree feeling, Greathouse says, was made possible by an internet that felt smaller and less performative. Back then, TikTok hadn't shortened our attention spans, Facebook was still where you updated your status to “in a relationship” and Instagram was a place where you were excited to get more than 10 likes on a post. Nine years ago, logging off didn’t mean escaping outrage cycles or influencer ads. It meant going back to real life.

“I liked when people wouldn’t be canceled off the face of the earth every five seconds. Certain people definitely deserved it, but it was a lot different,” says Greathouse. “You could be more open and say more stuff without people getting really, really upset about it.”

Gawfic agrees. “People just felt more accepting and real and cool at the time,” she says. “Things weren’t so picture-perfect, like the way we curate everything now.”

Nostalgia can be comforting, but it also serves as a shield against the uncertainties of the present. For many members of Gen Z, rewinding to 2016 feels safer than confronting a future marked by climate anxiety, political unrest and economic strain. Not because the past was perfect, but because it feels easier to understand. In a world overloaded with stimulation and curated realities, looking back is less about chasing trends and more about reclaiming a sense of authenticity. Whether they lived through it, missed it entirely or only saw it through a screen, Gen Z is searching for something that feels real in a world that often doesn’t.

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)