[10/10] is a series highlighting some of the music, movies and art we’re most passionate about.

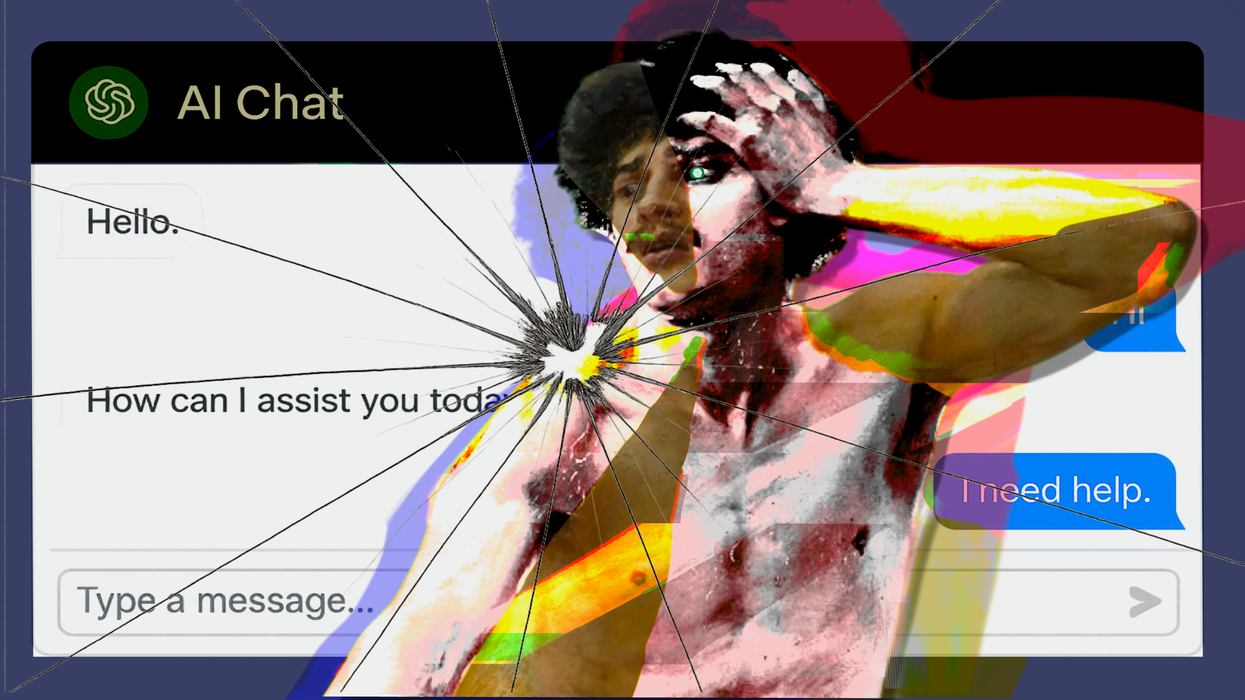

In tarot, the Hanged Man is strung upside down from the branches of a living tree, its roots reaching deep into the underworld. Suspended between realms, he sees what others cannot, a lone spiritual traveler who is adrift and uncertain. In La Chimera, his earthly counterpart is Arthur (Josh O’Connor), a British archaeologist caught in a liminal space where memory, mourning and myth intertwine. And fittingly, in the film’s promotional poster, he’s depicted as the Hanged Man, also adrift and uncertain.

Set in 1980s Italy, Alice Rohrwacher’s film is a sinuous, spellbinding tale that draws its magic from her esoteric and folkloric storytelling. Arthur is the portrait of spiritual exile, wandering the Tuscan countryside after the loss of his beloved Beniamina (Yile Yara Vianello), like Orpheus in search of Eurydice. Asleep, he searches for her in his dreams. Awake, he attempts communion by unearthing ancient Etruscan tombs, aided by a band of tombaroli graverobbers who rely on his preternatural ability to locate the dead with a dowsing rod. But where they see profit, Arthur sees beauty. He handles each artifact with reverence, quietly aware that they were never meant to be disturbed. And yet, he allows them to be stolen and sold.

Italy, a country with deep archaeological roots, has long been looted in the name of exploration and profit. In La Chimera, the tombaroli justify their theft as survival, feeding a system in which artifacts are funneled through shady middlemen like an opportunistic art dealer named Spartaco. It’s a familiar cycle in the art world: sacred spaces desecrated, beauty severed from its origins, artifacts traded to foreign collectors and museums. The film doesn’t moralize, but it does ask who owns the past. Or as one character astutely puts it, “Does it belong to everyone? Or does it belong to no one?”

La Chimera unfolds like a half-remembered dream, its narrative shaped by casual conversations, wordless gestures and wandering balladeers. Rohrwacher, working with cinematographer Hélène Louvart, shoots on 16mm and 35mm film, creating a textured, sensuous experience filled with fleeting nods to Fellini’s surrealism and Pasolini’s poetic lyricism. Yet Rohrwacher’s vision is entirely her own, rooted in the soil of Italian antiquity, while also remaining open to the hazy and mysterious influence of the spiritual realm.

Rather than follow a conventional plot, the film drifts — much like Arthur — through fragments of emotion, place and time. Its richness lies in its layering and the complex, often contradictory themes it explores. La Chimera meditates on love and loss, the sacred and the profane, the past and the present. But at its heart is a quiet critique of how capitalism reshapes our relationship to history, or what Rohrwacher calls “touristic exploitation of the past.” Sacred relics become mere commodities, stripped of meaning and context, bought and sold like any other object. And it’s a concern she knows intimately as a native Italian.

Capitalism has changed the way we relate to the world. It reduces everything to a commodity, and in La Chimera, that instinct is in overdrive. The tombaroli are exploited even as they exploit, pawns in a system where the upper class deals in millions, and they scrape by with crumpled lira notes. They labor in the shadows of shipping cranes and construction sites, unaware that they are both perpetrators and victims. They’re not just stealing history in this case; they’re being robbed of it too.

Arthur, by contrast, sees differently. Grief has turned him into an outsider, and that distance brings clarity. When he uncovers the statue of a goddess, he doesn’t sell her. He throws her head into the water, whispering that she was “never meant for human eyes.” As the others squabble over money, Arthur steps away, quietly insisting on another value system. One in which beauty, memory and the sacred are not for sale.

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)