“As all History must converge to Opera in the Italian Style, however, their Tale as Commemorated might have to proceed a bit more hopefully.” They are Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon, the English surveyors and astronomers who, between 1763-68, charted the eponymous border lines between Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware, made famous a century later as the invisible barrier between slave and free states, the fissure in the house divided. Thomas Pynchon’s 1997 novel Mason & Dixon is a frenetic epic of their America. As we approach the 250th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, and with it, an assured parade of reductive punditry about what it all means, Mason & Dixon will shake you with big questions. The competing maps of our national genesis myths are legible under its stars.

It is a series of folktales told in winter 1786 by a Philadelphian reverend. The narrative voice is his, replete with unconventional capitalization and grammar. (Do not be discouraged. It grows less distracting after a few chapters.) He knew Mason and Dixon, travelled with them on their Pennsylvanian expedition, and shares their stories to a shuffling crowd. The first third of the book explores the protagonists’ lives before America. A naval battle against the French upends their commission to observe the Transit of Venus from Sumatra. They visit Cape Town, hosted by slaving sex traffickers, then briefly make observations from St. Helena. In America they encounter Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson. In the wilderness their band of surveying associates expands, pulling the story on wild, discursive tangents. They feel the moral weight of their line-drawing mandate and probe the ethics of colonial expropriation. Starchart navigation connects them to a protean divinity. They move like oracles through an interlocking, at times tangled, narrative that fuses historiography, magical realism, folklore, socratic dialogue, and science fiction.

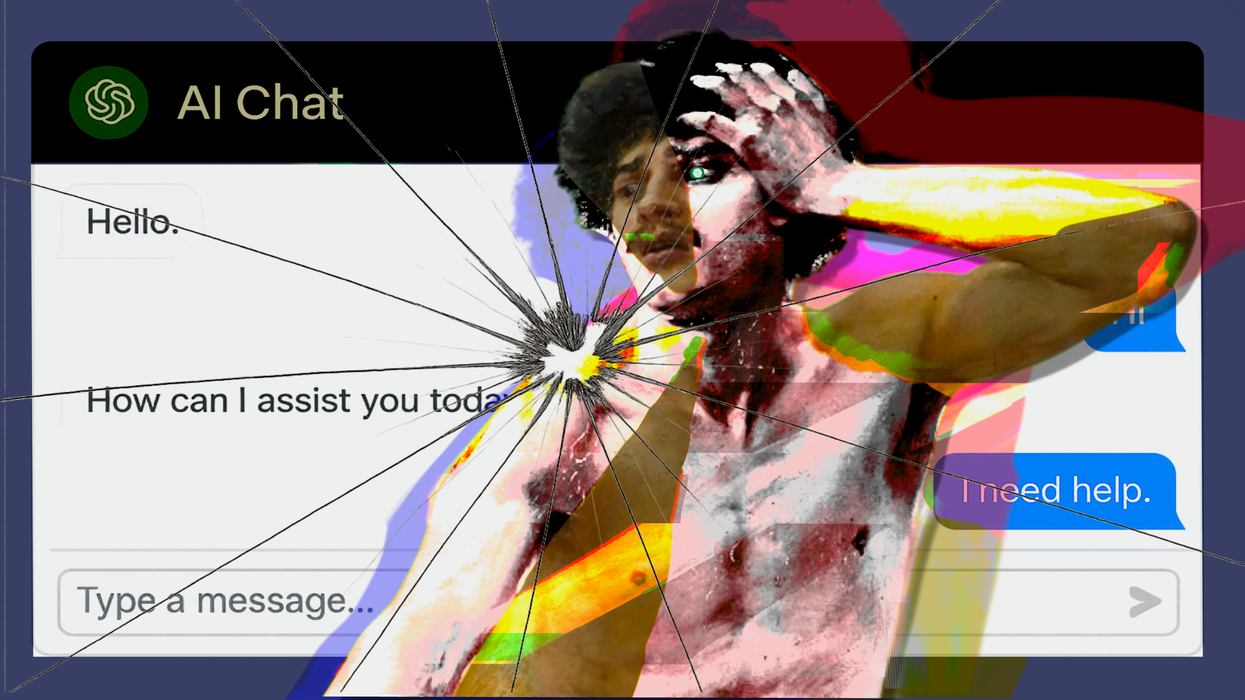

Today the American Right seeks to monopolize our founding myths. AI John Adams quotes Ben Shapiro. They’re scrubbing slavery from museums and textbooks. The Federalist Society’s originalism is the interpretive law of the land. The once-living Constitution is dead. All of this builds to the wet dream shared by the Christian Nationalists and tech bro anarcho-capitalists now running the show: that America is infallible because our culture is white and ordained by God. All contrary historical data will be flushed. It is a collective delusion of grandeur, an exceptionalism upholding that power is more important than truth. And it is winning.

When Justice Kagan wrote “we are all originalists now” she conceded that the constitutional spirit of America is frozen in amber, and that all battles for the future will be about the meaning of the past. Open Pynchon’s time capsule, dump it out, examine each chapter like a relic, and you’ll feel the complexity and disharmony of our national creation. There is no one myth. History is more scattered than fiction. The buzzwords of revolutionary America lose their emotional charge. Liberty, freedom, slavery, democracy, government, God – they’re all there, stripped of hero worship, unmilitant, held to the light. You will feel more and think more about the patriotic verities than ever before.

Mason and Dixon are aware that they are agents of conquest. Their border line —which they carve into the earth, clearing trees as they progress westward— anchors each of the characters, symbols, and ideas to the land. It is a meditation on manifest destiny at its genesis, yet stripped of romanticism, existentially spiraling, lost in the woods. They talk about violence as endemic to expansion. The Paxton Boys massacred peaceful Lenape. Dixon, disgusted with slavery, whips a slavedriver and liberates his captives. The ugly side of history is laid bare without swallowing the entire story. Violence unfolds with proportion, gaining abstract plenitude as the narrator explains “‘Unfortunately, young people, the word Liberty, so unreflectively sacred to us today, was taken in those Times to encompass even the darkest of Men’s rights,— to injure whomever we might wish,— unto extermination, were it possible…” What, then, were the bounds of liberty? What are they now? Does the Second Amendment mean - as the deified Charlie Kirk once argued - that some school shootings are worth it? Should we place any value in what liberty meant to men who systematically denied it to their slaves?

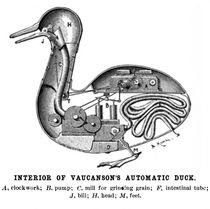

And what is God’s role in our national creation myth? It unfolds as metaphor. Vaucanson's mechanical duck gains full sentience, autonomy, and powers of invisibility and teleportation. It seeks to liberate another mechanical duck and avenge all its plucked, cooked brethren. To that end it stalks a French chef, who flees to America and joins the surveying expedition to escape it. The Duck floats in and out of the story as a God symbol. The chef recounts “I once would have inquir’d coolly, what an Automaton might know of Life, but now I only sat silent, unconsciously having assum’d what I later learned was that Hindoo asana, or Posture, known as “the Lotus.” At what moment the Duck may have taken her leave, who but the Time-Keeper knoweth? Time, however, had acquir’d additional Properties.” The quacking holy ghost judges and acts, a participant in the story, contrasted to the other great religious symbol, a giant golem, forged from the earth by Native hands, who is heard but never seen. In metaphor and in explicit dialogue throughout the book emerges this great Enlightenment preference of deism over theism. It is a rebuke to the Christian Nationalists who now claim that we the people were always evangelical. Au contraire. Jefferson thought Jesus a man, plain and simple. Thomas Paine wrote passionately about Deism as the guiding light of the Revolution. Franklin and Madison too averred that God did not play an active role in mortal affairs. Now Trump sells Bibles, and his cult of personality exalts him as chosen by God. Steve Bannon recently argued for a third term by labelling him a “vehicle of divine providence.” It is the logic of kings, the very logic indicted and purged by our revolution, now ascendant from politicized pulpits.

Questions of God, as they often do, lead to questions of religion. Ben Franklin instructs the title duo “Pennsylvania Politics? Its name is Simplicity. Religious bodies here cannot be distinguish’d from Political Factions.” The Quaker-Anglican-Presbyterian rivalries in Philadelphia follow the surveyors into the forests, where, lurking and scheming, subversive French and Native spies serve a cabal of Jesuits and Chinese mystics that Franklin deems “the two most powerful sources of Brain-Power on Earth, the one as closely harness’d to its Disciplin’d Rage for Jesus, as the other to that Escape into the Void, which is the very Asian Mystery. Together, they make up a small Army of Dark Engineers who could run the World” through the Jesuit Telegraph, a “Marvel of instant Communication… far-reaching and free of error, thanks to giant balloons sent to great Altitudes, Mirrors of para- (not to mention dia-) bolickal perfection, beams of light focused to hitherto unimagined intensities…” Was Marjorie Taylor Greene, when she ranted about space lasers and grand conspiracy, actually making a deep-coded Pynchon reference? No, but it’s wild fun to see the founding fathers consumed by their own Q-Anon-ish paranoia of a Sino-Jesuit syndicate. It is a protracted illustration that there has never been religious consensus and that the church-state barrier was purposefully created. Perhaps J.D. Vance and Clarence Thomas, who lead the charge to tear that barrier down and replace it with Christian patriarchy, would be humbled reading that they, as Catholics, are Ben Franklin’s great anti-American bugbear.

In the passage below, their line is drawn, and Mason and Dixon stand on a New York pier waiting to board for return passage to Falmouth, England. You feel that you are running out of pages, saddened that the philosopher friends are abandoning your land, never to return:

On their last visit to New-York, at the very end, waiting for the Halifax Packet, they dash all about the town, looking for any Face familiar from years before. Yet they are berated for their slowness at Corners. Carriages careen thro’ Puddles the size of Ponds, spattering them with Mire unspeakable, so that they soon resemble Irregulars detach’d from a campaign in some moist Country. The Sons of Liberty have grown even less hospitable, and there is no sign of Philip Dimdown, nor Blackie, nor Captain Volcanoe. “Out of Town,” they are told, when they are told anything.

“Let’s drink up and get out of here, there’s no point.”

“We can find them. That’s what we do, isn’t it? We’re Finders, after all.”

“The Continent is casting off, one by one, the Lines that fasten’d us to her.”

Yet at last, seated among their Impedimenta, Quayage unreckon’d stretching north and south into Wood Lattice-Work, a deep great Thicket of Spars, poised upon the sky, Hemp and City Smoak, two a shed-ful of somberly cloak’d travelers waiting the tide, they are aware once more of a feeling intra-cranial, part Skin-quiver, part fear,— familiar from Inns at Bridges, waiting-places at Ferries, all Lenses of Revenance or Haunting, where have ever converg’d to them Images of those they drank with, saw at the edges of Rooms from the corners of Eyes, shouted to up or down a Visto. This seems to be true now, of ev’ry Face in this Place. Mason turns, his observing Eye protruding in alarm. “Are we at the right Pier?”

“I was just about to ask,—“

“— I didn’t actually see any Signs, did you?”

They are approach’d by a Gentleman not quite familiar to them. A Slouch Hat obscures much of his Face. “Well met,” he pronounces, yet nothing further.

“Are ye bound for Falmouth?” Mason inquires.

“For Pendennis Point, mean ye, and Carrick Roads?” His tone poises upon a Cusp ’twixt Mockery and Teasing, which recognition might modulate to one or the other,— yet neither can quite identify him. “That Falmouth?”

“There is another, Sir?” Dixon, maniatropick Detectors a-jangle, gets to his feet, as Mason Eye-Balls the Exits.

“There is a Falmouth invisible, as the center of a circle is invisible, yet with Compasses and Straight-Edge may be found,” the Stranger replies. At that instant, the company is rous’d by a great Clamor of Bells and Stevedores, as the Packet, Rigging a-throb, prepares to sail. There will be perhaps two minutes to get aboard. “We must continue this Conversation, at Sea,”— and he has vanish’d in the Commotion. Each Day, on the Way over, Mason and Dixon will look for him, at Mess, at Cards, upon ev’ry Deck, yet without Issue.

Mason’s last entry, for September 11th, 1768 reads, “At 11h 30m A.M. went aboard the Halifax Packet Boat for Falmouth. Thus ends my restless progress in America.” Follow’d by a Point and long Dash, that thickens and thins again, Chinese-Style.

Dixon has been reading over his Shoulder. “What was mine then…? Restful?”

In the following chapter we imagine— what if they stayed? They chart the prairie and the desert. They discover Uranus. They are rejected by the country they made navigable, then retire to the mythical St. Brendan’s Isle.

I read the final chapter the day after I moved apartments in Philadelphia, boxes still a-clutter, assuming that we were en route to a pastoral English death finale— a placid, predictable conclusion. Instead I felt swallowed by a literary wormhole as Mason, chasing some final scientific discovery, returns to Philadelphia and dies on the very street I now call home. He is buried three blocks away from where I read the ending. I had no idea. These blocks will fill in the coming year with crowds exalting a quarter-millennium of something. Read Mason & Dixon if you need a reminder that it’s all more complicated than flags and fireworks. You get a say in what it all means. Ours is a map unfinished.

Trey Flynn is a lawyer in Philadelphia.

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)