This spring, I had a stomachache I couldn’t cure. Nothing I ate — or didn’t eat — seemed to help, not even the many cups of tea I drank or all the tabs of antacid I took. The only thing that worked was drinking, which was a telltale sign that the problem wasn’t in my gut. It was my anxiety over the launch of this magazine, a very public project I care about with sincere passion. And because of that, I was living in a constant state of low-key panic. I was absolutely petrified of the world thinking that I was cringe for doing this, and worse, with the most genuine of intentions.

Cringe is behavior or content that causes subjective secondhand embarrassment. It’s the mutual who overshares and the karaoke singer belting off-key. It’s the amateur editor posting their first video and the older person trying to act young. They’re the actions of painfully earnest people who appear a little too invested in what they’re doing, even if there’s ample room for improvement. They break an unspoken social code by trying too hard, taking up too much space and being too loud while doing it. And barring the cringe baiters who purposefully feed into this mockery for self-gain, the truly cringe lack a sense of self-awareness that makes it all the more embarrassing. We watch them and think: they should know better.

We’re all guilty of calling someone cringe and desperately trying to avoid that label ourselves. But then we also have to ask ourselves, why is it embarrassing to care? Why do we now avoid expressing our feelings with the honesty they deserve? And why do we hide our passion behind apathy, only willing to share if we package it as ironic? It’s probably because shrugging your shoulders will never offend or feel like too much, and so we censor ourselves for the comfort of everyone else. It’s a cop-out, but if that’s the case, why am I still scared of being unintentionally cringe?

People have always come together to witness the demise of others, which is why we love to gossip. It creates a sense of community, where we laugh as part of an in-group that knows better than to violate a certain social norm. But in the modern age, this tendency has been intensified tenfold, as demonstrated by endless cringe compilation videos and our obsession with turning every misstep into a meme. The internet has dramatically altered the consequences of being cringe, to the point where we’ve become terrified of the label and do whatever we can to avoid it.

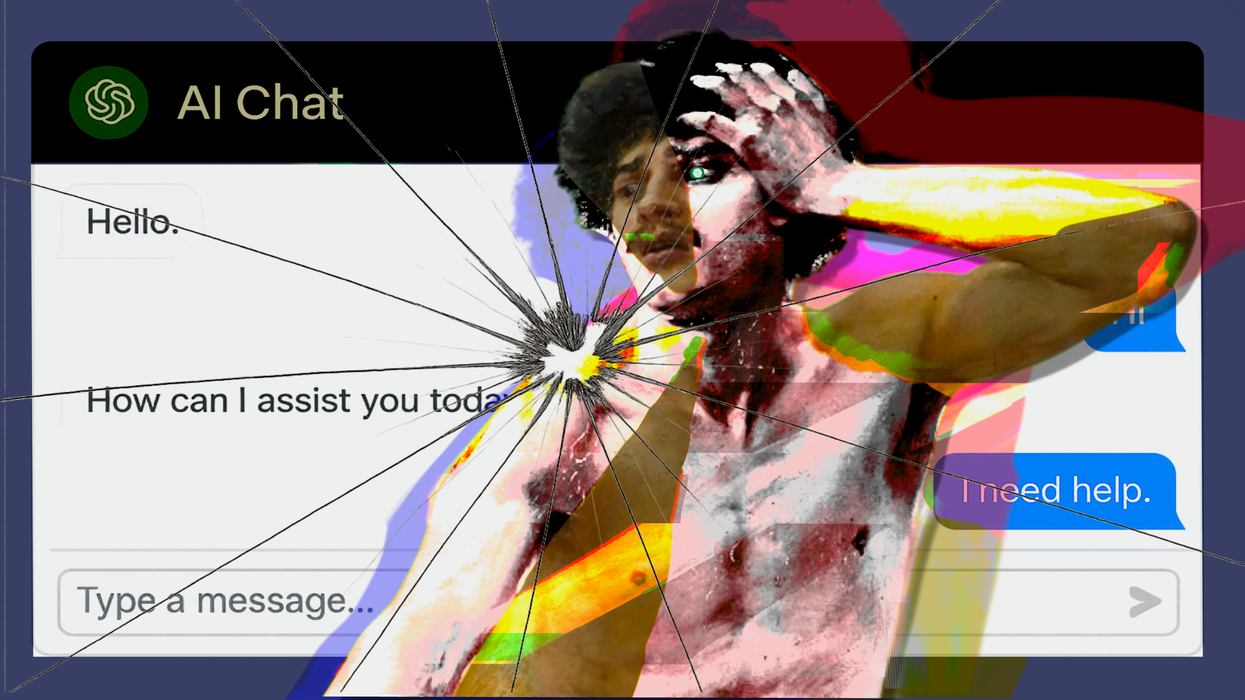

Being online has magnified the scale and scope of any humiliation. It has ensured your potential embarrassment is no longer isolated to a small set of witnesses, but may unintentionally go viral and live on forever as internet canon. Everyone will know you for all the wrong reasons, because you chose to do something that excites you and share that with the world. It makes it easy to be scared before you even begin, especially if it exposes a core part of you.

Cringe can be anything, but it always requires the creation of something. The problem is that creation is an already vulnerable process, with the end result being a deeply personal reflection of you. So when you’re creating a poem, a dance or anything else destined for public consumption, the fear of cringe is multiplied. The more passionate you are, the more painful it is to confront the idea of someone else’s laughter, and that can make it feel like it’s better not to try at all. It’s a great way to kill your creation in the cradle, and social media has only made this inclination infinitely worse.

With the threat of mass embarrassment hovering over our heads, the only way to protect ourselves from being laughed at online is to do nothing at all. Don’t be too loud and don’t say too much. Don’t experiment in case you accidentally do something weird, and definitely don’t care about something too much, because then it’ll hurt even more. Instead, study others and carefully curate what you put out into the world. Adhere to the unspoken social code that polices how you act and, by extension, what you create and share. Then, no one can ever call you cringe. They just won’t call you anything at all.

But to avoid cringe is to adhere to social norms meant to keep us quiet and complacent, which is even more reason to put ourselves out there. To be cringe is to be loud and genuine, to share yourself unapologetically without being scared of what the internet says. It’s having the guts to call bullshit on those who champion “authenticity” while actively trying to kill it with things like cringe. And most importantly, it’s about being brave enough to share a piece of yourself with the world, because it matters to you and fuck everyone else.

I’m far from “cured” when it comes to fully embracing cringe, but I’ve also stopped wanting to puke as soon as I start to write. I poured a lot of myself into this website and, last time I checked, that’s better than half-assing it. So without any sarcasm, I’m just going to go ahead and say that I do think it’s cool to be cringe, because it means I care. After all, the worst thing to feel is nothing, and I’d rather have a little stomachache.