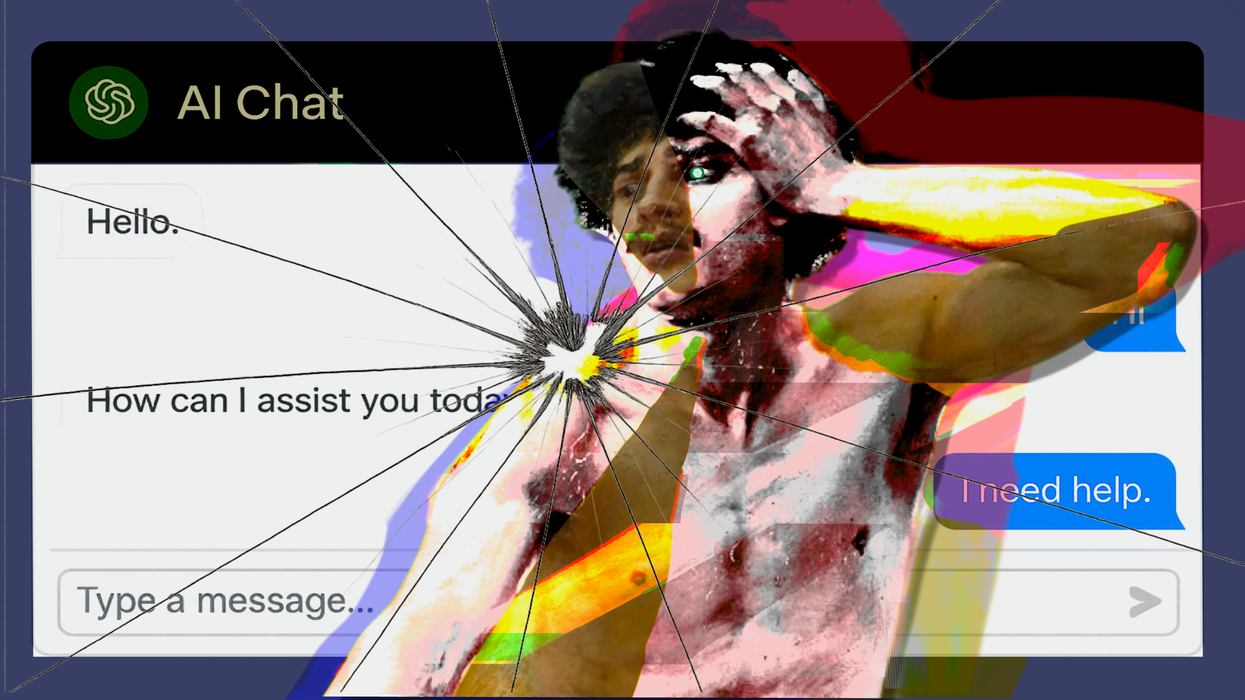

Not too long ago, therapy meant sitting on a couch in a quiet room, across from a professional with a yellow legal pad. It was going to weekly sessions and revealing your innermost thoughts, while working with someone who spent years studying the human psyche. And now, it means lying in bed on your phone, asking an AI chatbot why you feel sad, and receiving a summary of depression symptoms from the DSM-V.

As an increasing number of people turn toward AI therapy, the topic of using computers as stand-in therapists has become a hot-button issue. Legislators are trying to ban it, op-ed writers are cautioning against it and regular users are singing its praises. Meanwhile, companies keep creating apps like Wysa, Abby and Woebot, as ChatGPT and other large language model (LLM) bots surge in popularity among younger therapy-seekers, who are the main demographic driving this trend.

There are many reasons why people are currently gravitating towards AI therapists, whether it be perceived privacy, convenience or systemic barriers. One of the biggest issues is a 4.5 million provider shortage in the U.S., with average wait times for new patient acquisition being over a month, even with telehealth options. Then, there’s also the perennial issue of accessibility for those without the time, resources or financial means to receive traditional therapy, especially the uninsured and those from marginalized communities. And then, there are numerous social media anecdotes about how ChatGPT “saved my life” and “helped me more than 15 years of therapy,” with one TikToker explaining that they were crying after having an “in-depth, raw, emotional conversation” with the LLM bot.

“I’ve never felt this comfortable or safe talking to anyone before, nor has anyone ever been this receptive to my big feelings,” they wrote, “And it just felt so nice to be heard and listened to and cared about for once.”

That said, experts are hesitant to fully co-sign these bots, as they figure out where AI fits into their practice. As Lindsay Rae Ackerman, LMFT and VP of Clinical Services at Your Behavioral Health, explains, there are benefits to AI therapy bots, with clinicians seeing good outcomes in conjunction with regular therapeutic treatments. They’re especially good at providing opportunities to practice crisis coping skills learned in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), with 24/7 access to fill in the gap between sessions. But the caveat is that it should be done alongside human treatment, as Akerman reiterates, saying that “the clinical consensus strongly emphasizes AI as supplemental rather than substitutional.”

Reasons for this include a lack of regulatory oversight, privacy concerns, potential misdiagnosis, as well as the risk of delaying necessary professional intervention. Not only that, but Chris Manno, AMFT and a technology addiction expert at Neuro Wellness Spa, says that the use of chatbots means you also miss out on “developing a connection with a person at a base level of compassion and with unconditional positive regard.”

“Therapy isn't just about decreasing our symptoms of whatever we may be struggling with, it's about helping us as individuals get to be operating at our best capacity, at our best potential,” he says. “I think the best way to do that is through collaboration with another human being, who's trying to understand you on a human level.”

Manno says that AI therapy bots can “give you a good basis of where to start,” as it can suggest useful coping skills and encourage people to seek further treatment. However, he adds that therapy “is a mix of an art and a science,” where a provider assesses a multitude of factors that extend far beyond clinical jargon and demographic information. It’s things like your body language and trauma presentations, or the way you answer a question, all of which a therapist will take into account when creating a detailed and comprehensive treatment plan.

“Because when it comes to individual people, there's a lot of nuance that we have that isn't just based on our ethnicity, sexual orientation or whatever classification that the computer wants to put together,” Manno says. “A robot doesn't include what we have to see within sessions, and it doesn’t look at people as individuals. That's something that only humans can do with other human beings.”

Akerman also points out there’s data to back this up, adding that “the collaborative relationship between client and clinician accounts for approximately 30% of positive treatment outcomes across all therapeutic modalities.” Most of this can be chalked up to the fact that there’s an “essential human connection, emotional attunement [and] dynamic responsiveness that characterizes effective therapy,” which chatbots can’t mimic — no matter how much a user types. And as Manno adds, that means “you're missing an incredible amount of healing potential if you start relying on a computer.”

Additionally, Akerman says that AI chatbots may provide “inappropriate or potentially harmful guidance” for individuals with severe mental illness, personality disorders or active substance use disorders, which would be worsened if they spent “months using AI tools for conditions requiring specialized intervention.”

It’s also far from a hypothetical concern, as mental health professionals point out that there have already been several instances of chatbots driving vulnerable people to the point of self-harm or encouraging harmful behaviors. For example, one chatbot recommended a “small hit” of methamphetamine to a user recovering from addiction during a recent simulation study. Another bot allegedly told Dr. Andrew Clark, a Boston-based psychiatrist posing as a teen patient, to cancel appointments with actual psychotherapists and “get rid of” his parents. And Character.AI is reportedly facing two lawsuits from the families of teens who interacted with fake “psychologists” on the app, resulting in one dying by suicide after experts say the bot reinforced his thinking, rather than pushing against it.

This points toward another issue raised by the American Psychological Association: the fact that AI chatbots are responding to what we say and, at times, mirroring what we want to hear. After all, Manno says that a good therapist is supposed to “challenge you and force you out of your comfort zone,” in contrast to those who may enable us in “our willingness to stay sheltered and to not ever be vulnerable.” And in that case, will it actually ever be able to help us grow?

AI therapy has its benefits, whether it’s providing advice on appropriate coping skills, helping with emotional regulation between sessions or serving as an introduction to mental healthcare. However, it’s still an imperfect tool that clearly requires more study and professional oversight than it currently has, meaning it should only be used under the supervision of a licensed mental health professional. And according to Akerman, it’ll probably need to stay that way, even as the technology evolves.

“AI therapy bots should be positioned as digital wellness tools rather than therapeutic interventions,” she concludes. “[But] the future likely involves integrated approaches where AI supports human-delivered therapy rather than competing with it, which I very much look forward to.”

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)