Today, I can go online and, in two clicks, I can find any type of music I want. I can obsess over it. I can become friends with strangers who like the same thing from thousands of miles away.

I can immerse myself in whatever I want, wherever I want, whenever I want. I can be an expert in any specific thing. I can link with people who know more about that thing than I could ever imagine. And in a couple of hours, I can become truly knowledgeable in whatever I want and look the part if I really tried. Then tomorrow, I can do the same thing but with something else.

I was asked to write this article because I run Emo Nite and said some shit like “emo was the last genre,” thinking it sounded cool as a quote but knowing I was probably wrong. The more I think about it though, the more I feel like it’s accurate. Emo was the last genre before the internet gave everyone the unlimited access pass. It made it easy to be everything and nothing, and with that, we lost the sense of identity that comes with really caring about something.

I can’t think of something that’s come out in the last 20 years that emo didn't touch one way or another. Of course, other styles of music have also inspired new genres — not to mention emo before emo existed — but emo was the last genre that changed the world before the internet made it easy to be anything and anyone with one click. It was the last genre of influence before we lost the entire culture of having to commit to something bigger than ourselves. Where we had to really work to be a part of something, without shortcuts like Wikipedia or Spotify.

When I was growing up, it took years of dedication to learn everything about a certain genre. It was usually during those high school years, which is that formative time when you discover what you like, what you hate, who your friends are, what they think is cool, what they think sucks ass and what music you listen to. And with emo, it was the last time people cared to work offline to be a part of something. It was based on digging for, listening to and learning about the music, because coming together to the sound of emo was something special. It made things meaningful.

Sometimes, it took years to find your community, but when you found it, you found it. I would look at eras like the ‘60s, ‘70s, and ‘90s and know exactly what that looked like in my head without being there. Each time period was so distinct, to the point where I can say “‘80s,” and you know what that sounded and looked like.

I was actively looking for that “thing” I could look back on and say “ah, the old good days.” At the time, I thought my era sucked. I thought my culture was going to the mall. But as with most things, time has proven me wrong. I now look back at 2002 to 2015 with more fondness every day. Because every day we stray further and further away from not only those memories, but also the thought that the world might get a chance at experiencing that again. And it all boils down to one simple thing: the internet.

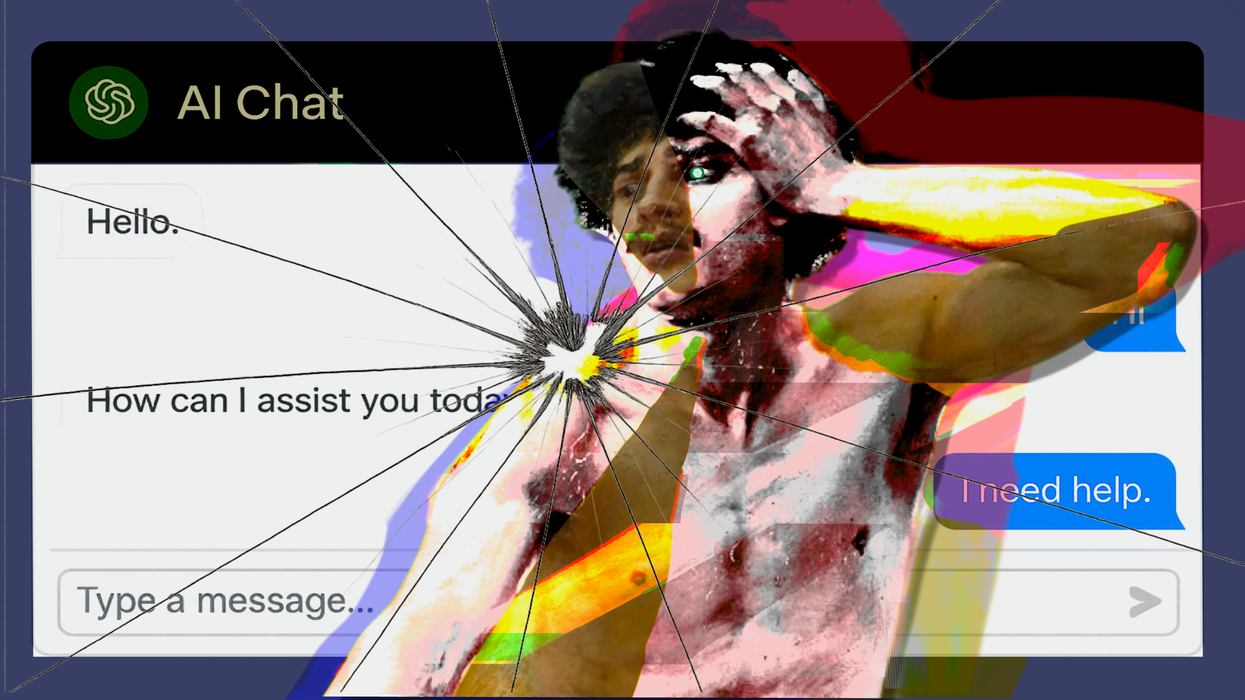

While emo was the music that was getting passed around on torrenting sites like Limewire and Napster, it was also the last time you had to really dig to find something. A lot of the time, those tracks didn't even have a name (or it was wrong). I loved the song “dnjgfnjls” that played in my CD player until it broke. I was heartbroken because I didn't know who that artist was. I thought I had lost something that meant so much to me and would never be able to find it again, because I simply didn't know anything about who it was or how that CD ended up in my car. I had lost a piece of me. Today, I can Shazam and know it’s a Her Space Holiday song. Boom. Done. But the emotional bond grows weaker and weaker between the listener and the song.

Today, you don’t need to seriously commit to anything. Don't know who Title Fight is? Give it three minutes, and the internet will tell you everything you need to know. It can tell you why they broke up, their importance, who they influenced, who they're dating, who they’re friends with, who they follow, what they ate for breakfast. Growing up, this could take years, if at all, to find out. You had to be motivated, you had to leave your house to find like-minded people, and you had to care. And because you cared, that made it important, that made it meaningful.

While I do think there are aspects of this online world that are awesome, I do think it’s changed the sense of finding your community and connecting over something you had to work for. I'm not saying shit sucks now. I'm just saying there hasn't been any entire genre with an actual identity that has come about since. There's nothing that we can't all point our fingers back at and say, "There's some Saves the Day in there, even if it's way down there." It might be harder to find in some styles of music than others, but it's there, and nothing can change the fact that emo was the last genre before we all knew too much to care.

There are some things I do love the internet, though. I love being able to reference shit I would have never been able to see unless I visited a museum. I love that I can meet a stranger across the world and truly be connected with them through a joke. I love that if I like a certain artist, I can find every artist associated with them, inspired by them and who they’ve inspired in five minutes tops. The beautiful thing about the internet is that we can know everything. But there's also a sad truth: if it's so easy to listen to and be anything, why care about it if you can just change what that is tomorrow?

Morgan Freed is the co-founder of Emo Nite and Ride or Cry.