At the height of Love Island USA season 7, new episodes were only half the entertainment. As each one aired, the fun came with recapping, discussing and dissecting the Islanders’ every move on social media. But that conversation quickly went south, as some viewers began diagnosing contestants like Huda Mustafa with borderline personality disorder (BPD). As Mustafa’s relationship with Jeremiah Brown shifted from lovey-dovey moments to screaming call-outs, more and more people piled on with amateur commentary. And in the era of armchair psychology, Love Island contestants aren't the only reality stars under this kind of scrutiny.

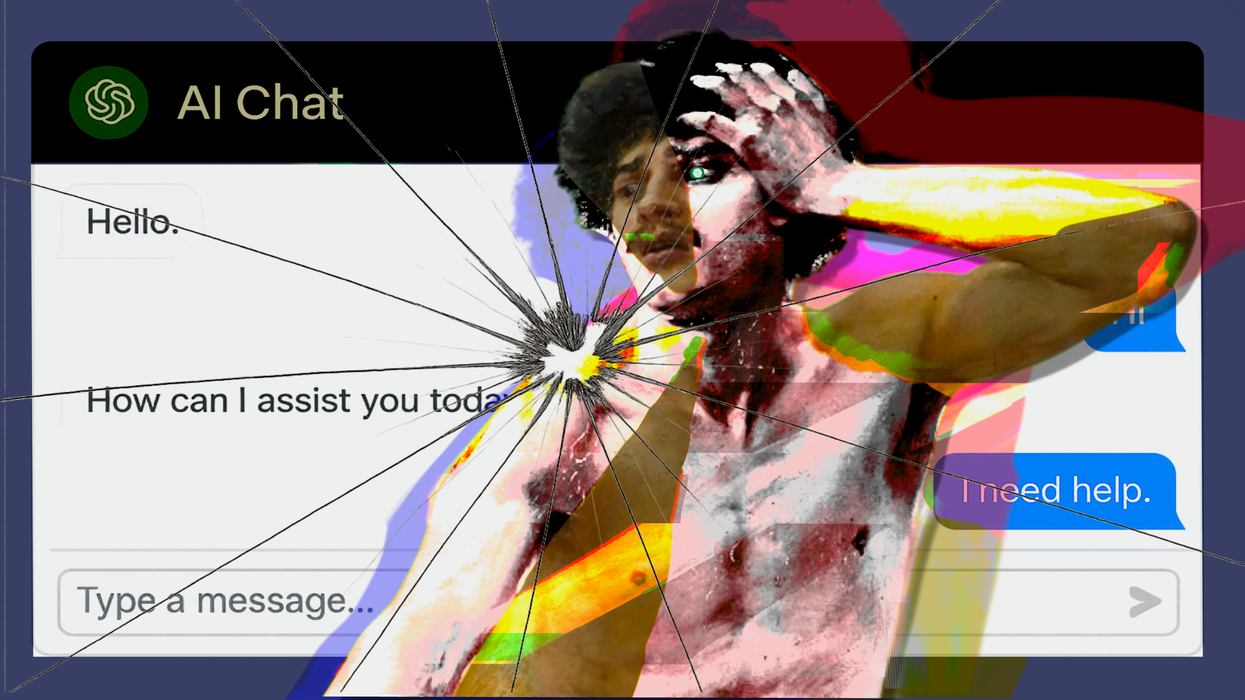

With social media breeding a new kind of fan culture around surveillance-based reality shows like Love Is Blind, Big Brother, The Ultimatum and Love Island, a different entertainment experience has emerged. Audiences don’t just watch people on reality shows anymore; they try to diagnose them.

On Reddit, Threads, TikTok and X, posts dissect contestants’ attachment styles, speculate on personality disorders or note signs of trauma responses. Stans and at-home commentators throw around psychological buzzwords like “gaslighting,” “avoidant,” “love bombing” and “narcissist,” assigning them to the behavior of complete strangers. But they’re only seeing a small slice of these people, who are often being hyper-performative or cast as a certain archetype like “The Villain.” There’s also editing — reality television’s not-so-secret weapon — which purposefully makes it so that we don’t see the nuances of a person or situation. So how do viewers truly know whether someone actually has or is experiencing one of these issues? And why are they so quick to judge?

@kierabreaugh Replying to @jinglewingle #loveislandusa ♬ original sound - Kiera Breaugh

Then, there’s the manipulation factor. Reality shows often rely on 24/7 filming and social isolation, which heightens drama and creates unrealistic scenarios where things play out in ways they typically wouldn’t. Placing participants in controlled environments, they amplify conflict and foster messy interactions between participants. In Love Is Blind, for example, carefully selected contestants are isolated from the outside world, proposing marriage based on emotionally charged conversations before seeing their partner for the first time. Then, when things go sour, viewers are quick to diagnose: She has anxious attachment. They’re a narcissist. There’s so much trauma bonding.

Sometimes, they’re right, but there are also dangers to doing this without proper expertise. Not every toxic moment is narcissistic abuse, and not every tear is trauma. However, over-identification with the exaggerated moments shown on reality TV has still led to people diagnosing these strangers and, at times, themselves and others. Of course, there’s no issue with being self-aware or a concerned friend, but this can unintentionally lead to bigger issues. According to experts, armchair diagnoses can cause unnecessary stress and anxiety, delay proper intervention, increase stigma and diminish the experience of those who’ve survived true psychological abuse.

But while some of this analysis is certainly shallow or misinformed, it also reflects a deeper cultural shift. In some ways, reality TV has become a mirror, reflecting viewers' own emotional patterns back at them. By labeling and analyzing someone else’s behavior, viewers are able to create emotional distance while also gaining tools to understand their own patterns better. For many people, watching a castmate spiral on national TV can be the first time they recognize a behavior in themselves. For example, seeing a contestant repeatedly forgive bad behavior in the name of “love" — or even “like” — may prompt viewers to ask: Do I do the same thing in my relationships?

Love is Blind can be dumb but this scene where a man’s separated parents discussed their son’s fear of commitment (due to witnessing father’s philandering) was kinda powerful pic.twitter.com/5zNW5IUD2u

— lele (@lelequelindo) March 7, 2024

Even with its pitfalls, the impulse to analyze others and ourselves signals something important: people are hungry for self-understanding. Though these shows are made for entertainment, the impact can be deeply personal. In a world where therapy is still expensive and inaccessible to many, reality TV can become an unlikely entry point into emotional introspection. In a way, this new way of consumption has become an unorthodox form of group therapy. But at the same time, it's worth asking if reality TV can be trusted to mediate reality.

![[10/10] La Chimera: A Dreamlike Descent Into Grief, Memory and Myth](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61454821&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C1%2C0)