[10/10] is a series highlighting some of the music, movies and art we’re most passionate about.

In 1977, Johnny Carson ruled nighttime television. For fifteen years, the Nebraska-born comedian had hosted NBC's The Tonight Show, essentially inventing our modern late-night format with the monologue, the desk, the celebrity couch and the band off to the side. By 11:30 PM each weeknight, roughly 15 million Americans were watching Carson crack wise about politics and flirt with starlets. His sidekick Ed McMahon's nightly introduction — "Heeeere's Johnny!" — had become as reliable as the national anthem.

That same year, Brian Wilson sat in his bedroom, strung out on cocaine and psychiatric medication, watching Carson religiously. The man who'd given us endless summer had locked himself away in an endless night. Wilson's world had shrunk to the dimensions of that room, where he'd spend days in bed, paralyzed by voices that cursed him "all day every day." During this time, The Tonight Show became his nightly mass.

From this devotion came "Johnny Carson," which was allegedly written in twenty minutes of raw creative urgency, as if hesitation might let self-consciousness creep in and destroy the gesture's purity. In Wilson's absence, we're left where he was then: alone with only "Johnny Carson" to light the way.

Listen to it. Really listen. Those opening keyboard chords don't sound like music. They sound like furniture being dragged across linoleum. The Moog synthesizer doesn't so much play notes as emit distress signals from 1977's loneliest suburb, wheezing and groaning like a dying robot trying to remember what melody used to mean. It's the aural equivalent of fluorescent lighting at 3 A.M. It's harsh, unforgiving and absolutely real.

The production is raw to the point of discomfort. That single cymbal crashes on repeat, stabbing through the mix like someone dropping a tray in a library. The bass line thuds along with the musicality of a heart monitor. Every element feels wrong and cheap, broken like a skipping record. Session musicians would have smoothed out these edges, added professional sheen. But Wilson was post-smooth. Post-sheen. Post-1977. This was just him, his Moog, and whatever was left of his mind. So we get the sound of genius operating on fumes and Radio Shack equipment — accidentally creating lo-fi music twenty years before suburban garage bands discovered fuzz pedals

Above the whirly-gig production is the flattened voice of Mike Love, Wilson's cousin and the Beach Boys' lead vocalist. Except this isn't the Mike Love of "California Girls" or "Fun, Fun, Fun." His vocal delivery lies somewhere between a news anchor and a sedated patient, methodically reciting basic facts about a man at his desk until the bridge, when the song commits its greatest act of strange beauty. Suddenly, the words turn into fragments of broken syllables, with Wilson breaking them apart until language itself starts to malfunction. It's unsettling in the way that mannequins are unsettling. It's almost human but fundamentally wrong.

But it's the outro that achieves transcendence through repetition. The full Beach Boys harmonies that once served as the soundtrack of American optimism kick in for a cheerleader chant that loops into infinity. They ask who's the man they admire before declaring Carson a "real live wire", a refrain repeated over and over and over, like an obsessive thought. It should be annoying. Instead, it's hypnotic.

Critics have spent decades trying to quarantine "Johnny Carson" as a novelty track. Even Carson himself responded with characteristic Midwestern dryness: "I think they just did it for the fun of it. It was not a work of art." But Carson, the consummate entertainer, couldn't recognize that Wilson wasn't trying to entertain. He was trying to exist.

The verses obsess over Carson's routine with anthropological precision amid the desk, the microphone and the network's demands. When that outro arrives and Wilson has the Beach Boys chant "Johnny Carson is a real live wire" into oblivion, it's not a celebration, it's an incantation. He's trying to manifest normalcy through repetition, to sing stability into existence.

This asymmetry deepens the melancholy. Here was Wilson, who once conjured "Good Vibrations," now on the other side of the screen, looking up at someone who could still perform the nightly miracle of showing up.

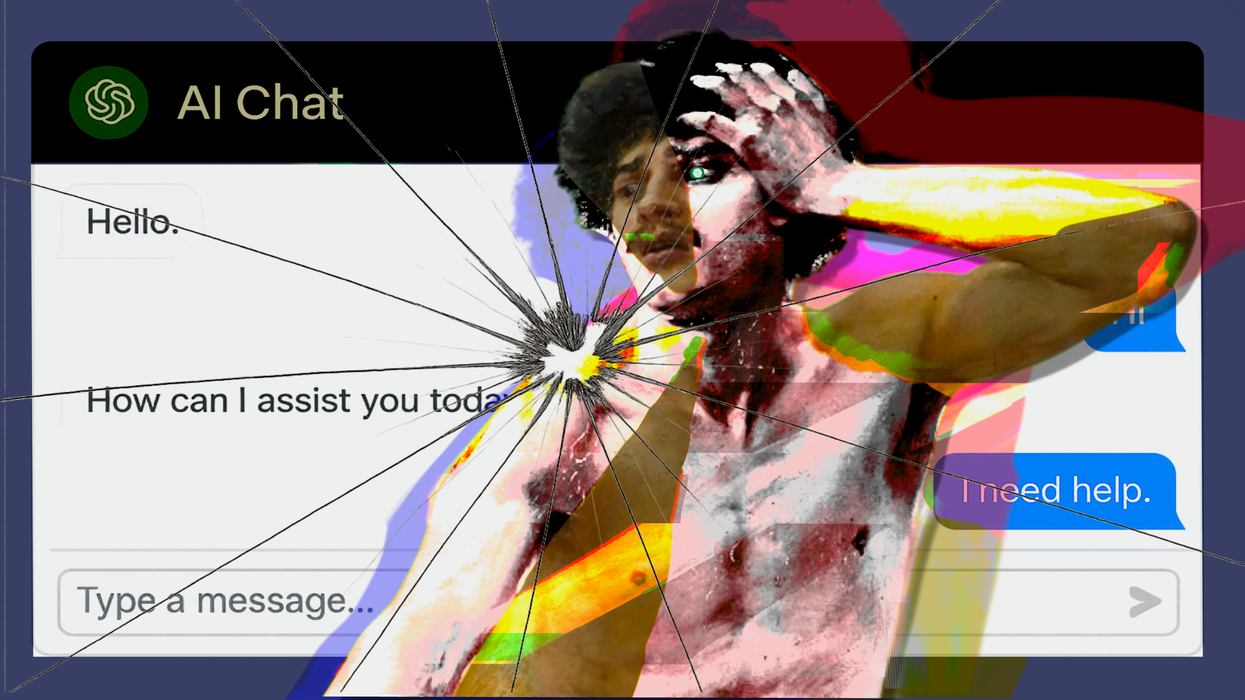

"Johnny Carson" isn't an admiration of fame or comedy or genius. It's a song that's obsessed with someone reliable, which Wilson needed as his world spun increasingly out of control. In many ways, "Johnny Carson" is the first parasocial relationship committed to tape, decades before we had a term for it. Wilson's fixation on Carson prefigures our current loneliness epidemic perfectly: the desperate intimacy we build with strangers on screens, the way reliability becomes its own form of love. Every night at 11:30, Carson showed up. Every night at 11:30, Wilson watched. Routine became ritual, ritual became religion.

In our age of curated vulnerability and algorithmic authenticity, "Johnny Carson" stands as a monument to what genuine artistic torment sounds like. This isn't performative weirdness or focus-grouped eccentricity. It's the sound of a man whose genius had curdled into obsession.

Nearly fifty years later, "Johnny Carson" feels less like a curiosity and more like prophecy. It's almost like Wilson accidentally documented the future of human connection in all of its mediated, obsessive, achingly sincere and completely one-sided sadness. In an era of livestreamed breakdowns, of people finding their only constant companions in YouTube personalities who upload daily or Twitch streamers who never log off, Wilson's fixation on Carson reads like the first dispatch from our collective future.

Now Wilson is gone, and "Johnny Carson" remains in its beautifully ugly perfection. It's the sound of loneliness before we had Instagram to prettify it, back when isolation still sounded like cheap synthesizers and desperation. Some art shows us who we could be. "Johnny Carson" shows us what we are: confused, desperate creatures seeking stability in the cold glow of screens, mistaking reliability for love and finding the divine in the gap between commercial breaks.

![[10/10] The Visceral Sincerity of The Beach Boys' "Johnny Carson"](https://vextmagazine.com/media-library/image.png?id=61430866&width=1245&height=700&quality=90&coordinates=0%2C0%2C0%2C0)